The Art of Walking Smoothly: Remembering the Sony Discman and the Great Lie of “Anti-Skip Protection”

Today, you have 50 million songs in your pocket on a device thinner than a pencil. You can run a marathon, do backflips, or skydiving, and the music will never stop. But in the mid-90s, if you wanted to take your digital music with you, you needed cargo pants, a backpack full of AA batteries, and a high tolerance for frustration.

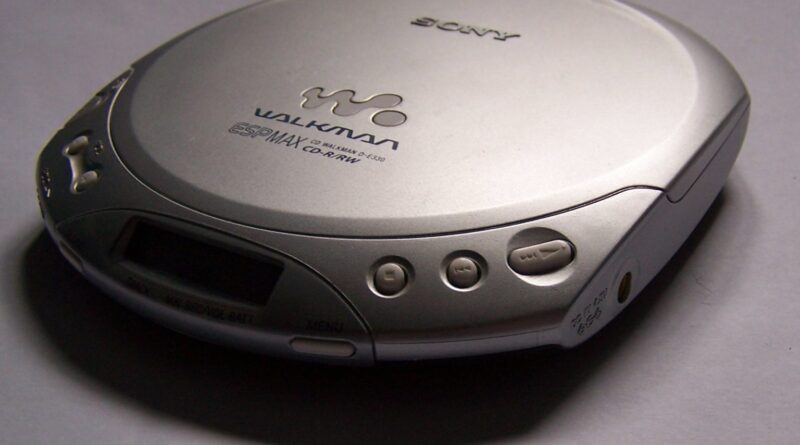

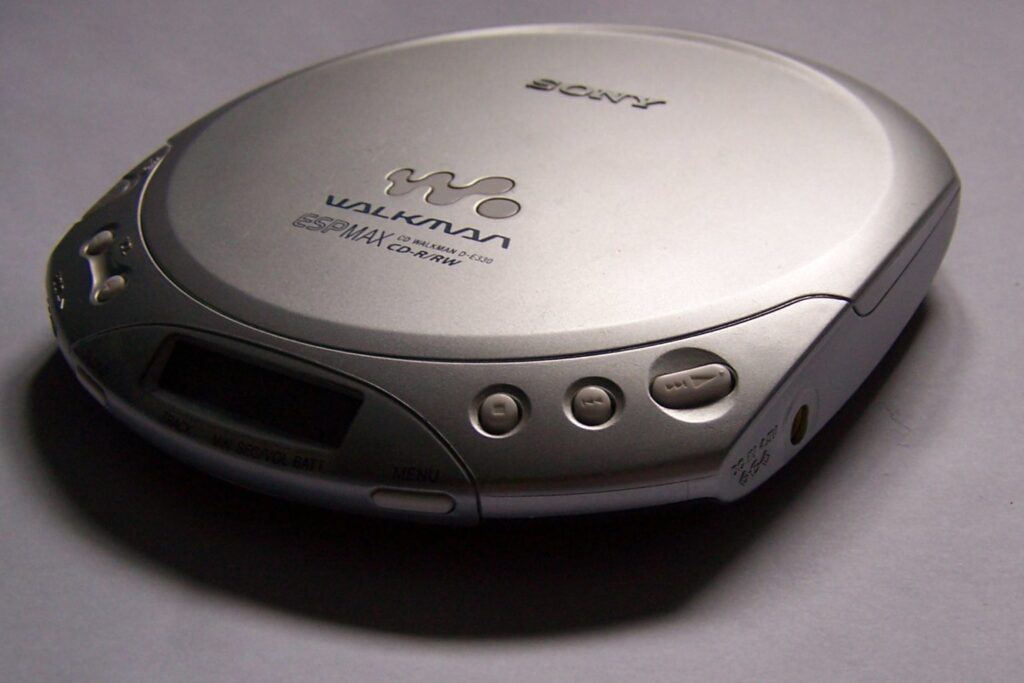

Enter the Discman. The successor to the legendary cassette Walkman, it promised the crystal-clear digital sound of the Compact Disc. But it came with a massive, fatal flaw: It hated movement. It was a portable device that punished you for being portable.

Lasers vs. Gravity: The Engineering Flaw To understand why the Discman was such a nightmare, you have to understand the physics. A CD player works by spinning a plastic disc at 500 RPM while a tiny laser reads microscopic pits on the surface. The tolerance for error is less than the width of a human hair.

Now, imagine trying to thread a needle while riding a roller coaster. That is what the Discman was trying to do every time you took a step. If you jogged, it skipped. If you hit a speed bump on the school bus, your favorite Nirvana track would stutter like a scratched vinyl (“Smells like teen… teen… teen… spirit”). We all developed a weird, smooth way of walking—keeping our upper body perfectly still like a waiter carrying a tray of soup—just to keep the music playing.

The Lie of “Electronic Shock Protection” (ESP) Sony and Panasonic knew this was a problem. So, they introduced a magical button: ESP (Electronic Shock Protection). The marketing claimed it made the player “Jog Proof.” This was mostly a lie.

Here is how ESP actually worked: It didn’t stop the laser from shaking. Instead, it spun the disc faster to read ahead, storing about 10 to 40 seconds of music in a digital memory buffer (RAM). If the laser bumped, the player would play the music from the memory chip while the laser frantically tried to find its place again.

- The Catch: Once that 10-second buffer ran out, the music died anyway.

- The Cost: Turning on ESP drained your batteries twice as fast because the motor had to spin at double speed. It was a choice between “Skipping Music” or “Dead Batteries.”

The Binder Burden (Case Logic) And let’s not forget the accessories. You didn’t just carry the player. You had to carry your library. In the Spotify era, we have playlists. In the Discman era, we had Case Logic Binders. These were massive, zippered nylon books filled with plastic sleeves. A serious music fan would carry a 48-disc binder in their backpack.

It weighed about 5 pounds. You looked like you were carrying nuclear launch codes, but it was just the complete discography of Pearl Jam and The Offspring.

- The Tragedy: If you lost your phone today, you lose a device (data is in the cloud). If you lost your CD binder in 1999, you lost your soul. Hundreds of dollars of music, gone forever.

The Battery Struggle The Discman was a vampire. It fed on AA batteries. If you were rich, you bought Duracell. If you were a normal teenager, you bought the cheap generic batteries that lasted about 45 minutes. There was a specific sound a Discman made when the batteries were dying. The song didn’t just stop; it slowed down, turning the singer’s voice into a demonic, deep-pitched groan before the LCD screen faded to nothing.

The “MP3 CD” Era: The Final Form Just before the iPod killed it, the Discman had one final evolution: The MP3 CD Player. Suddenly, you could burn 100+ songs onto a single CD-R using your computer. You didn’t need the binder anymore! But navigating 150 songs using a tiny LCD screen with “Next/Back” buttons was a UI nightmare. It was too little, too late. The hard drive revolution was coming.

Conclusion The Discman was flawed, bulky, fragile, and expensive to run. But it was ours. It was the bridge between the analog hiss of cassette tapes and the digital freedom of the iPod. It taught us to value our music because we literally had to carry the weight of it on our backs. So, we salute you, you skipping brick. You were terrible, but we loved you anyway.

Read Also: The Artificial Sun: Why Nuclear Fusion Is the Holy Grail of Clean Energy