The Artificial Sun: Why Nuclear Fusion Is the Holy Grail of Clean Energy

For decades, scientists have chased a simple, almost divine dream: What if we could put the Sun in a box? The Sun produces heat and light not by burning coal or gas, but by smashing atoms together at terrifying speeds. This process is called Fusion. It is the engine of the universe.

For the last 70 years, we have tried to replicate this on Earth. We failed. We could only manage Fission (splitting atoms), which gave us nuclear power plants. While efficient, Fission creates dangerous radioactive waste that lasts for thousands of years and carries the risk of catastrophic meltdowns like Chernobyl or Fukushima.

Fusion is different. It creates zero long-term radioactive waste. It carries zero risk of meltdown. And its fuel is found abundantly in seawater. It is the infinite energy “cheat code” for civilization. And for the first time in history, the Artificial Sun is actually rising.

The “Always 30 Years Away” Joke For a long time, Fusion was the laughing stock of the physics world. There was a running joke: “Fusion is the energy of the future… and it always will be.” Scientists claimed it was “30 years away” in the 1970s. They said the same in the 1990s. Skeptics believed it was physically impossible to get more energy out of the reaction than we put in to start it.

But recently, that joke officially died. In a historic breakthrough at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California, scientists at the National Ignition Facility (NIF) achieved “Ignition.” For the first time ever, they fired 192 giant lasers at a tiny pellet of fuel and generated more energy from the fusion reaction than the laser energy used to spark it. The laws of physics didn’t change; our engineering finally caught up.

Fission vs. Fusion: Why It Matters To understand why this is a holy grail, we must distinguish it from the nuclear power we know.

- Fission (Old Nukes): You take a heavy atom (Uranium) and split it. It releases energy but leaves behind a toxic, radioactive mess. If the machine breaks, the reaction can run out of control (Meltdown).

- Fusion (The New Way): You take two light atoms (Hydrogen isotopes: Deuterium and Tritium) and smash them together to make Helium. Helium is harmless; it’s the stuff inside party balloons.

- Safety: Fusion is incredibly fragile. If something breaks or the power goes out, the reaction just… stops. There is no meltdown. There is no fallout. It is inherently safe.

The Two Paths: Lasers vs. Magnets Right now, there is a global race to build the first commercial reactor. There are two main approaches:

- Inertial Confinement (The American Way): Using massive Lasers to crush the fuel pellet instantly. This is what NIF used to achieve ignition.

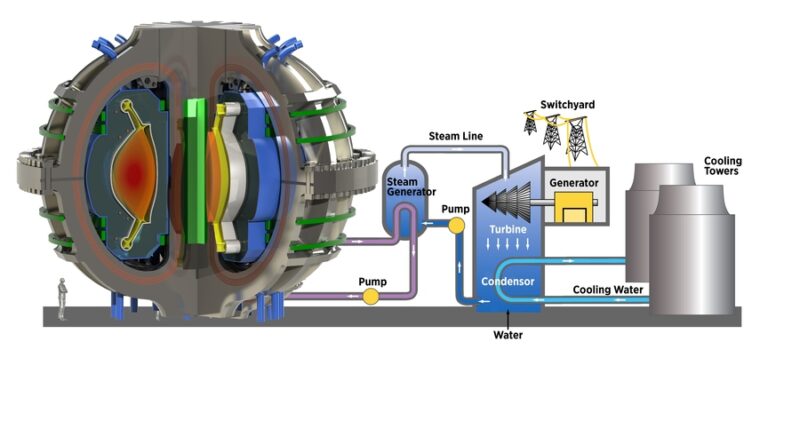

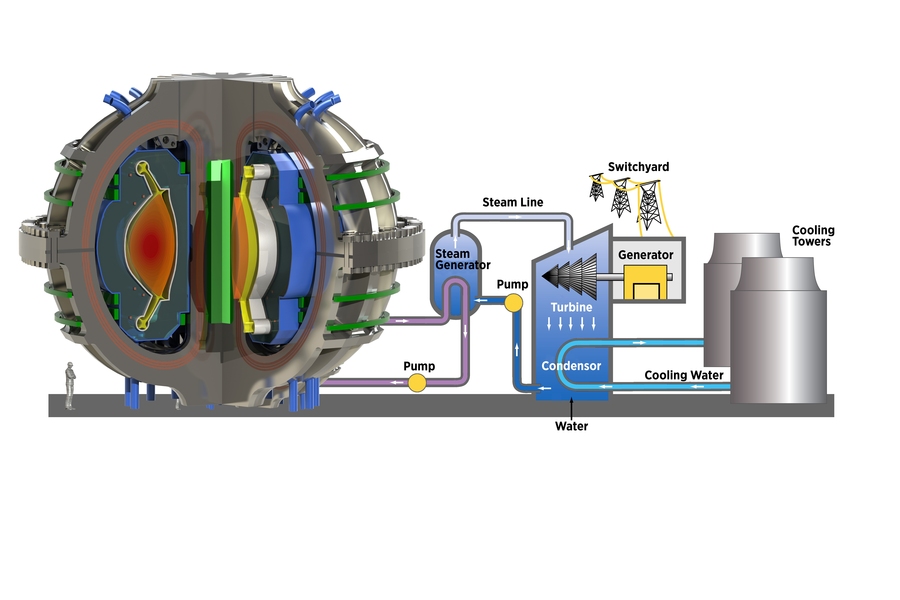

- Magnetic Confinement (The International Way): Using giant donut-shaped machines called Tokamaks (like the ITER project in France). They use powerful magnets to float super-heated plasma that is hotter than the core of the sun.

While governments are building the big machines, private startups like Helion Energy and Commonwealth Fusion Systems (backed by Bill Gates and Sam Altman) are racing to build smaller, cheaper reactors by 2030.

(H2) What This Means for Us (The Economics) If we can commercialize this, the world changes overnight.

- Cheap Electricity: The cost of energy drops to near zero.

- Water Abundance: We can use the excess energy to desalinate ocean water cheaply, solving the global water crisis.

- Carbon Zero: We can shut down every coal and gas power plant on Earth. Climate change isn’t solved by “using less”; it is solved by “using better.”

The Reality Check: From Lab to Grid We must remain grounded. Achieving ignition in a lab for a fraction of a second is like lighting a match. Building a power plant is like building a campfire that burns forever. The engineering challenges are immense. We need materials that can withstand heat hotter than the sun for months at a time. We need to figure out how to harvest that heat efficiently.

We are not going to plug our phones into a fusion grid tomorrow. But for the first time, the timeline isn’t “30 years away.” It’s closer to a decade.