The Pocket Tyrant: How Tamagotchi Taught an Entire Generation Anxiety (and Prepared Us for Smartphones)

Before we had Slack notifications to give us work anxiety. Before we had “Read Receipts” on WhatsApp to give us relationship anxiety. Before we had the constant ping of social media… we had the Tamagotchi.

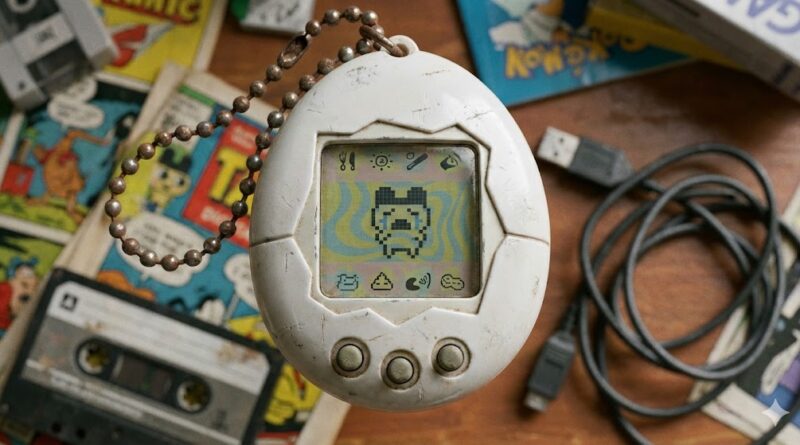

Released by Bandai in Japan in 1996 and the rest of the world in 1997, this egg-shaped plastic keychain was a global pandemic long before COVID. It was marketed as a “Virtual Pet.” But in reality, it was a relentless, beeping tyrant that demanded attention 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. It was the first time in history that humans became subservient to a piece of silicon.

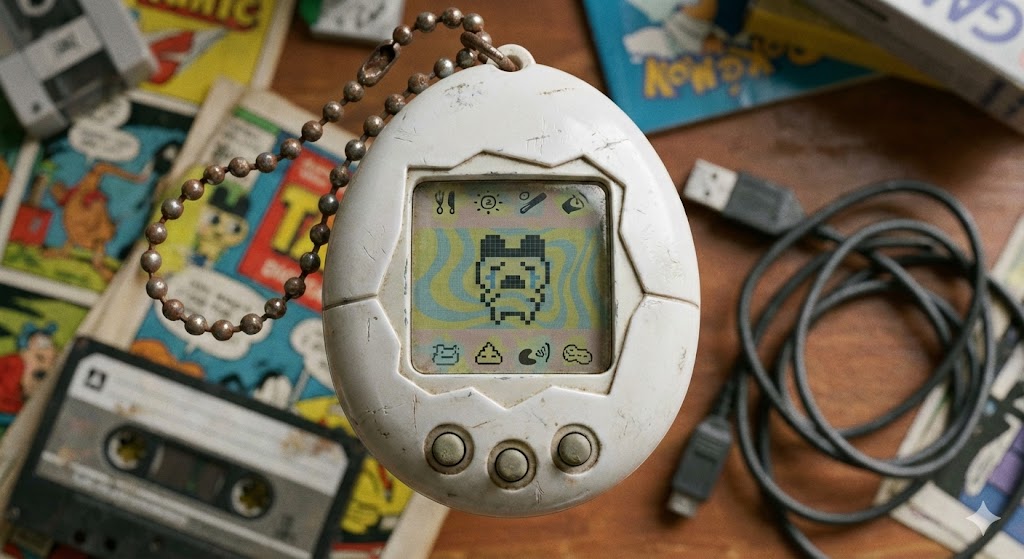

The Mechanics of Stress For Gen Z readers who missed this craze, the premise was deceptively simple. You pulled a plastic tab to activate the battery. An egg appeared on the blurry LCD screen. After 5 minutes, it hatched. Then, the nightmare began.

You had three buttons (A, B, C). You had to feed it meals (but not too many snacks, or it would get sick). You had to play games with it to keep it happy. And most importantly, you had to clean up its pixelated poop. If you failed? It didn’t just get sad. It died. A skull and crossbones would appear on the screen, accompanied by a grim, final beep. For a 10-year-old, this was a traumatic lesson in mortality.

The “Tamagotchi Effect”: Emotional Attachment Psychologists were baffled. Why were children crying over a $15 piece of plastic? This was the “Tamagotchi Effect.” Humans are hardwired to care for things that appear helpless. The device used simple algorithms to manipulate our empathy. When it beeped, you had to check it. Not because you wanted to, but because you felt guilty.

There were reports of “Tamagotchi Cemeteries” appearing online. In Hungary, a dedicated graveyard was created for people to bury their dead devices. It was mass hysteria over a few lines of code.

Banned in Schools: The First Distraction The stress was real. If you ignored your Tamagotchi for a few hours during Math class, you would check it at lunch only to find a digital tombstone. As a result, kids were checking their pockets every 5 minutes. Teachers went to war. Schools across the US and Europe banned them. They were confiscated by the thousands. This created a black market economy: “Tamagotchi Sitters.” Kids would pay other kids (or beg their stay-at-home moms) to babysit the device during school hours just to keep the creature alive.

The Precursor to the Smartphone Era Looking back from 2025, we realize something profound: Tamagotchi was a training program. It was our first taste of “Push Notifications.”

- The Tamagotchi beep is the ancestor of the Instagram notification.

- The “Hunger Meter” is the ancestor of the “Battery Anxiety.”

- The fear of it dying is the ancestor of “FOMO” (Fear Of Missing Out).

It trained an entire generation to constantly reach into their pocket to check a small screen. It conditioned us to respond immediately to digital stimuli. When the iPhone launched 10 years later, we were already addicted to the loop. We just traded the pixelated alien for a Facebook feed.

The Resurrection: It Never Died Believe it or not, Tamagotchi never went away. Bandai kept making them. Now, due to the [Analog Rebellion] and Y2K fashion trends, they are making a comeback. The new versions (Tamagotchi Uni) connect to Wi-Fi and have a metaverse. But original, unopened 1996 units are selling on eBay for hundreds of dollars. Collectors want to buy back a piece of their childhood trauma.

Conclusion We kept them alive for a week. They died. We cried. And then we hit the reset button to do it all over again. The Tamagotchi was a simple toy, but it changed how we interact with technology forever. It taught us that digital objects could hurt our feelings. And to be honest, I still hear that phantom beeping in my nightmares.

Read Also : Why Your Wallet Will Be Empty in 2026 (The Rise of CBDCs and “Programmable Money”)